A friend and colleague recently sent me pictures of their museum visit of the day: panels, and more panels filled with text and images. The subject of the exhibition – slavery – was quite relevant to our everyday lives. Which makes such lazy interpretation, if we can call it that, just that much more unacceptable. An exhibition is not a book, after all.

In 2022, I blogged about storytelling history. A recent visit to the National Maritime Museum of Korea in Busan has made me think more generally about the importance of mise en scène of exhibitions.

Mise en scène

Mise en scène is defined by film director Amy Aniobi as ‘setting the scene. It’s the composition; how the story can be told by what you see.’ Screenwriter Anna Klassen says that mise en scène‘fills in the narrative details’ beyond words, making it ‘the life force of any narrative: it’s the color [sic], the texture, the culture of the scene.’ [1]

Note that mise en scène supports stories and narratives, which is what I argue exhibitions should be. A story, it may be worth pointing out, is more than the traditional interpretive theme [2]. It can encompass different narrative strands and perspectives and also include contradictions. A story takes people on a journey of discovery and understanding, without being overly concerned with the (one) meaning they should walk away with.

Mise en scène used well

The story of the exhibition at the Maritime Museum in Busan explored people’s life with the sea in superbly sequenced rooms on their responses to it. Here were their writings, both in literature and daily life, their art, the ways in which they used the sea’s materials to furnish and beautify their homes. Then there was the transition out onto the sea, with another room on fishing and the equipment needed for it. Up until here, the presentation was mostly standard, with objects in cases, but smartly selected to prioritise quality over quantity. Text was to the point and rather poetic (which may just be thanks to the language, not the interpretive approach).

It was when I turned the corner and entered the room on maritime exploration that mise en scène really made the difference.

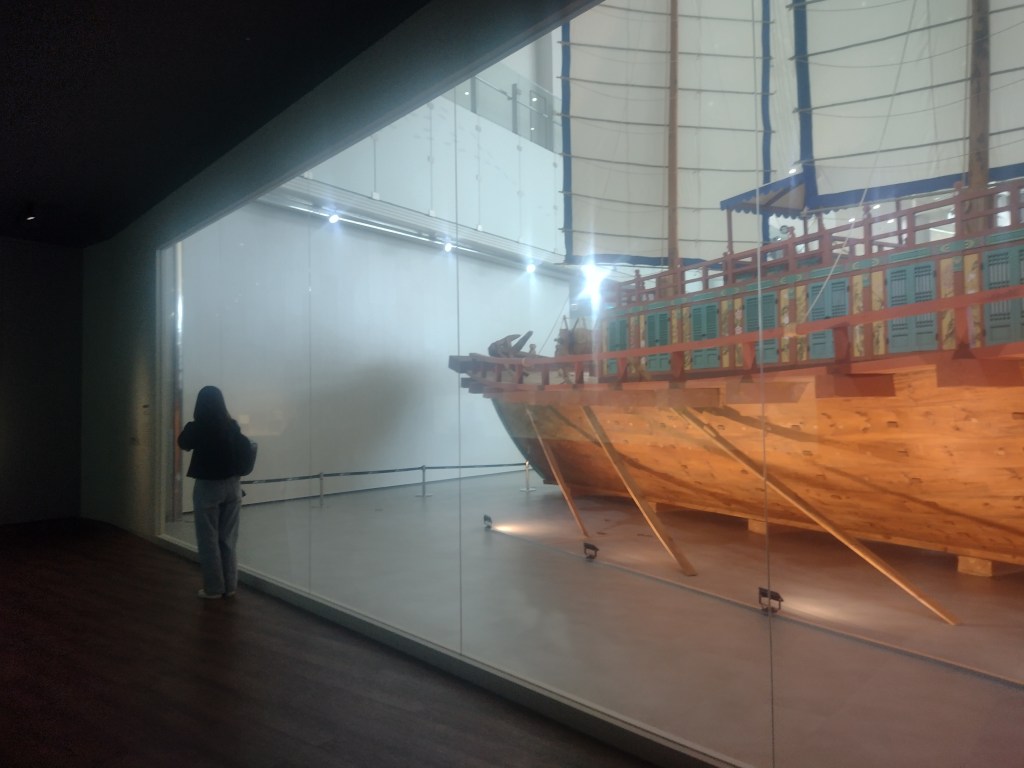

The animated, floor-to-ceiling screens gave the immediate sensation of being out on an unknown sea, reflecting the spirit of exploration to which the room was dedicated. The abstracted waves made it more emotionally involved, representing the sea as both beautiful and dangerous. This was enhanced by the sounds of crashing waves, which intriguingly made me feel cold, as if I’d been drenched with water. The models of ships from various countries and ages were beautifully lit and seemed to come alive in this imagined seascape.

This worked. And it made the previous rooms somehow better, too, because it built and reflected back on how we’d just seen people experience the sea. Now it was our turn to respond with all our senses.

This is what good mise en scène can achieve. It stages the story. Space, light, sound, smell all become communication devices around the object as a prop. Done well as was the case here, very few words are needed, which in a diversity-conscious context is always a good thing. Nor does mise en scène always have to be as elaborate as in the example above. The following images are from the same exhibition and show that a little bit of thought given to mise en scène can go a long way.

Notes

[1] Source: Lutes, A., 2023. What Is Mise en Scène? A Guide to Impactful Visual Storytelling. Available at: https://www.backstage.com/magazine/article/mise-en-scene-definition-examples-75967/. Accessed: 30.05.2024

[2] Professionally trained interpreters will be familiar with Freeman Tilden’s writing on giving form to specialists’ knowledge in his book Interpreting Our Heritage, which subsequent writers like Sam Ham and John Veverka have developed further into themes, understood as the main idea that reveals the meaning of the heritage being interpreted (see for example this essay by David Larsen from 2008, hosted on the website of the National Park Service, accessed 30.05.2024).