I have recently read the book Das Neue Lernen heißt Verstehen (New Learning means Understanding) by German neurobiologist Henning Beck. He develops the idea of understanding as the goal of learning from the study of how our brains work. Scholars like David Perkins [1] have developed a similar concept of understanding as performance from studying students’ learning within Higher Education.

Both argue that learning is far more than reproducing facts. Not so very new a thought, you may say, except that most approaches to teaching still prep and assess learning by administering conventional tests. If learning is understanding, however, then the assessment is a performance of that understanding in a new context that requires stretching one’s ability toward the creation of new knowledge. This also has consequences for teaching, and thus were born the principles of Teaching for Understanding [2], which form the core of my current studies in Teaching and Learning in Higher Education at University College Cork.

When I recently visited the Musée Lalique in Wingen-sur-Moder in France, I was reminded of this literature on learning as understanding (performances). The museum makes excellent use of games that truly get visitors to perform their understanding, and in doing so, gets them to learn about René Lalique’s jewellery and glass art of the last century.

I’m not talking about the usual interactive that lets you click on a pretty picture which thus expands and tells you more about a piece. They had versions of that, too, but the one I spent some time with went a step further and made visible the net of practices – architecture, fashion, lifestyle – that provided the context to Lalique’s work. This visual schema is still stuck in my mind several days later along with the information it transported about how the aesthetics that fuelled Lalique’s designs were shared in all aspects of life in the late 1920s.

The games, however, set you a clear task. In the first one I did, this was to place Lalique’s jewellery on the correct spot on what was the outline of a person. Once you placed it correctly, a window popped up confirming what you had already guessed, i.e. what the piece was (a brooch, a bracelet etc.). This was a fairly simple set-up, but very effective in getting you to look closely at the pieces and experience the variety of jewellery that Lalique had created. It also taught you about jewellery that perhaps you didn’t know existed, such as the corset applications.

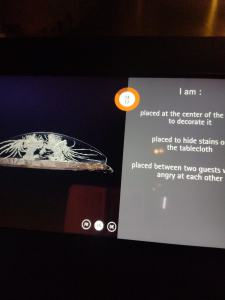

Another game asked you to complete a multiple choice quiz about tableware. I liked this even more than the first, because not only did it tell you about the pieces but also about table setting in the early part of the 20th century. Some of the answers made it very easy to guess the correct one, but this gave it a playful feel as the nonsensical options were also very funny. At the end you received your score and could go back to improve if you wanted to.

Importantly, these games were not geared toward children. Children could and did complete them, too, but nothing about the games made them specifically for one audience. The many adults I watched doing the games without any children in sight confirm what Henning Beck’s book on how the brain learns also suggests: no matter their age, human brains learn well through a game-like approach.

I am still not one who promotes an understanding of interpretation as primarily learning. However, I do think there are moments when facilitating learning can be a legitimate goal of interpretation. René Lalique’s work was one such moment and the use of games was very successful. It created the insecurity that Henning Beck talks about as one important criteria for learning. The games didn’t test for facts that had been given elsewhere; rather, they scaffolded your guess work on the basis of knowledge you were likely to already possess. It was fun and instructive, and I really hope more museums take this route in the future, of facilitating understanding performances rather than reducing humans to what Beck compares to machine learning.

Notes

[1] Perkins, D. (1998) ‘What is understanding?’, in Stone Wiske, M. (ed.) (1998) Teaching for Understanding. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 39–57.

[2] In a nutshell, these principles focus on what it is within a discipline that students are required to know in order to produce new knowledge later on. The principles also require teachers to be transparent about what exactly it is that students should know and be able to do after a class. A central method of teaching is to facilitate performances of students’ understanding. These performances must be set so that they not only show what has been learnt, but increasingly require students to stretch that knowledge and create new knowledge(s).

The connection between learning as performance and museum interpretation is particularly compelling. I love how the Musée Lalique’s games went beyond traditional interaction to truly engage visitors in contextual thinking. It’s a great example of how understanding can be deepened through active participation. The blend of playfulness and intellectual challenge makes the experience memorable and, as you point out, resonates with learners of all ages. I hope more museums adopt this approach—it’s a brilliant way to bridge education and entertainment while respecting the diverse backgrounds of their audience.