The current issue of the British Museum Association’s Museum Journal features an article about the American Museum of Natural History in New York. In it, it makes mention of what sounds like an incredible piece of interpretation focusing on the connections within the natural world that are too small for us to see with our own eyes: Invisible Worlds is an immersive experience which, according to Lauri Halderman, the museum’s vice president for exhibitions, at certain moments in the 12-minute-loop also responds to visitors’ own movements within the space and thus makes their own connection to those worlds visible.

It sounds perfect. I love how the museum appears to have taken the core fact about our world – everything is interconnected – and really thought about what type of interpretative medium could enable visitors to experience that, especially given the challenges of minute scale or speed. The images from the immersive environment look amazing as they seem to blur the distinction between visitors and the natural world. In this surround projection of enlarged DNA molecules and time-manipulated focus, connections not only become visible, they dominate visitors’ senses and enable them to have both a physical and I imagine emotional reaction. This is interpretation at its best, when it becomes the very thing it tries to make visible: Invisible Worlds itself is a connection, involving visitors on more than just the intellectual level.

These are the kinds of immersive experiences I think work. They are more than just a fancy way of re-displaying existing art.

A fancy re-display is unfortunately how I experienced the main display at the Van Gogh Exhibition in York recently. While the venue, a former church, added some interest to the projections, that’s really all they remained: projections of paintings occasionally bleeding out over the entire wall. Since in the case of Van Gogh particularly, the physicality of his brush strokes and the paint piled high on the canvas are such an intrinsic aspect of his work, this left me wondering throughout what a projection as a medium was meant to do. The sporadic voice-over very often simply repeated quotes that had already been projected, so there was no interplay happening there either. This was not interpretation, and I don’t know if it wanted to be. But it also was no artistic rendering of the paintings in a different medium, a re-telling that added something new. This, it felt, was projection for projections sake, and it was disappointing.

Very far from disappointing, however, was the Virtual Reality journey through Van Gogh’s paintings in the same exhibition. This was truly immersive, as Virtual Reality always is, and it did open up a completely different opportunity not just to see, but to be in the paintings, to feel a part of their landscapes, to look around and act within them. The audio, from what I remember – I was a bit distracted by the visual sensation – did provide explanations as to what one saw, and this, I felt, worked well as a useful interpretive encounter. It wasn’t great storytelling, but it was the kind of re-imagining in a different medium that most decidedly provided a new perspective.

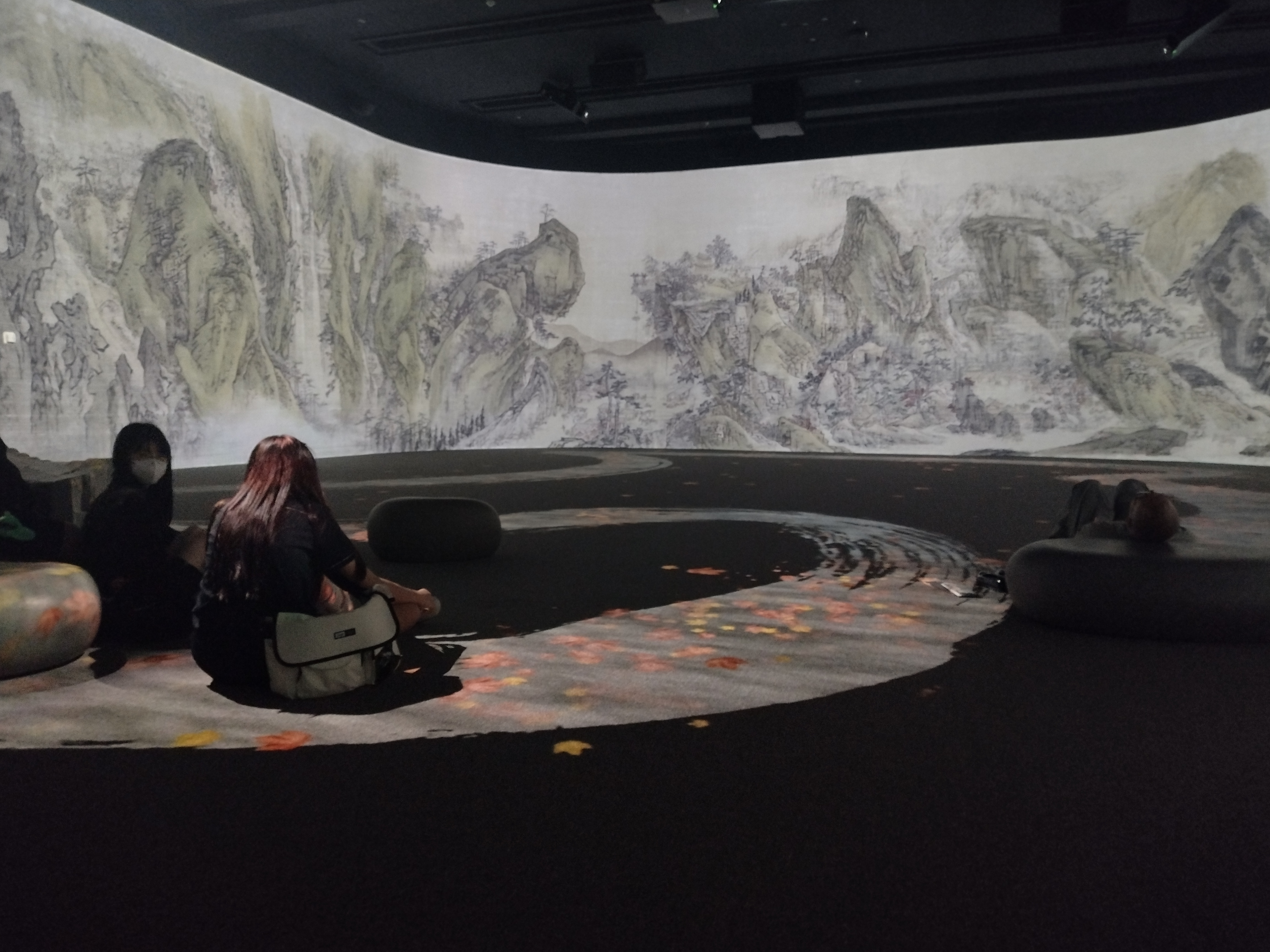

Fantastic Interpretation at the National Museum of Korea: without words,using only the narrative power of Yi In-Mun’s scroll and enhancing it through an immersive animation.

I saw really great storytelling within an immersive experience at the National Museum of Korea. Its disappointingly called ‘Immersive Gallery 1’ is focused on traditional art which is animated across a 60m by 5m panoramic screen. It didn’t stop there, however. The presentation of Yi In-Mun’s scroll Endless Mountains and Rivers, for example, took a moment frozen in the painting, of a father and his family, and from this spun a story: we follow him through the scroll’s landscapes, join him as he meets other people in the scenes of everyday life captured in the scroll, and we finally rejoice with him as he returns home. This is fantastic interpretation: without words, using only the narrative power of the scroll itself and enhancing it through an immersive animation. Thus the visitor is seamlessly, joyfully guided through the beauty of the Joseon landscape that Yi In-Mun sought to capture along with the culture of the people living within it.

As I think about good interpretive immersive experiences, I do want to also mention the Battle experience at the Culloden Battlefield Visitor Centre when it first opened in 2008. Technologically, this may feel less slick today, but it worked: visitors were physically placed in the middle of the battle as it unfolded in projections onto the four walls that surrounded them. It was confusing, it was at times frightening, and it was emotional. It worked. Visitors would repeatedly refer to it in conversations with us and pointing out how this is what made people’s experiences real to them.