I admit it: despite my qualms about stately homes and the way they tend to be interpreted, they are still my most favourite places to visit. Thus I came upon Burton Constable Hall in Yorkshire, and what a delight it was – really good interpretation included.

Management

Burton Constable Hall is owned by the Burton Constable Foundation, a charity which was established in 1992. The charity does not own any other properties, so its sole focus is on Burton Constable Hall [1]. I think this may be one of the reasons why the place had a very personal and authentically local feel to it.

The Facilities

Having said that, the facilities (and the interpretation – I get to that in a bit) were all to a very high standard and comparable to what one may be used to from country-wide organisations [2]. I particularly liked the café, which to my delight allowed dogs indoors and offered a table service to bring your coffee and food. Non-dog owners may not notice the difference, but this simple gesture improved my sense of welcome manifold upon arrival [3].

The Building and Collections, Or: the absolute joy of place

What really blew my mind, however, were the building and its collections. The rooms at Burton Constable Hall are magnificent in their sheer size and the vistas they offer. Add to that the collection of furnishings and art original to the house, and this visit became one of the most aesthetically joyful ever.

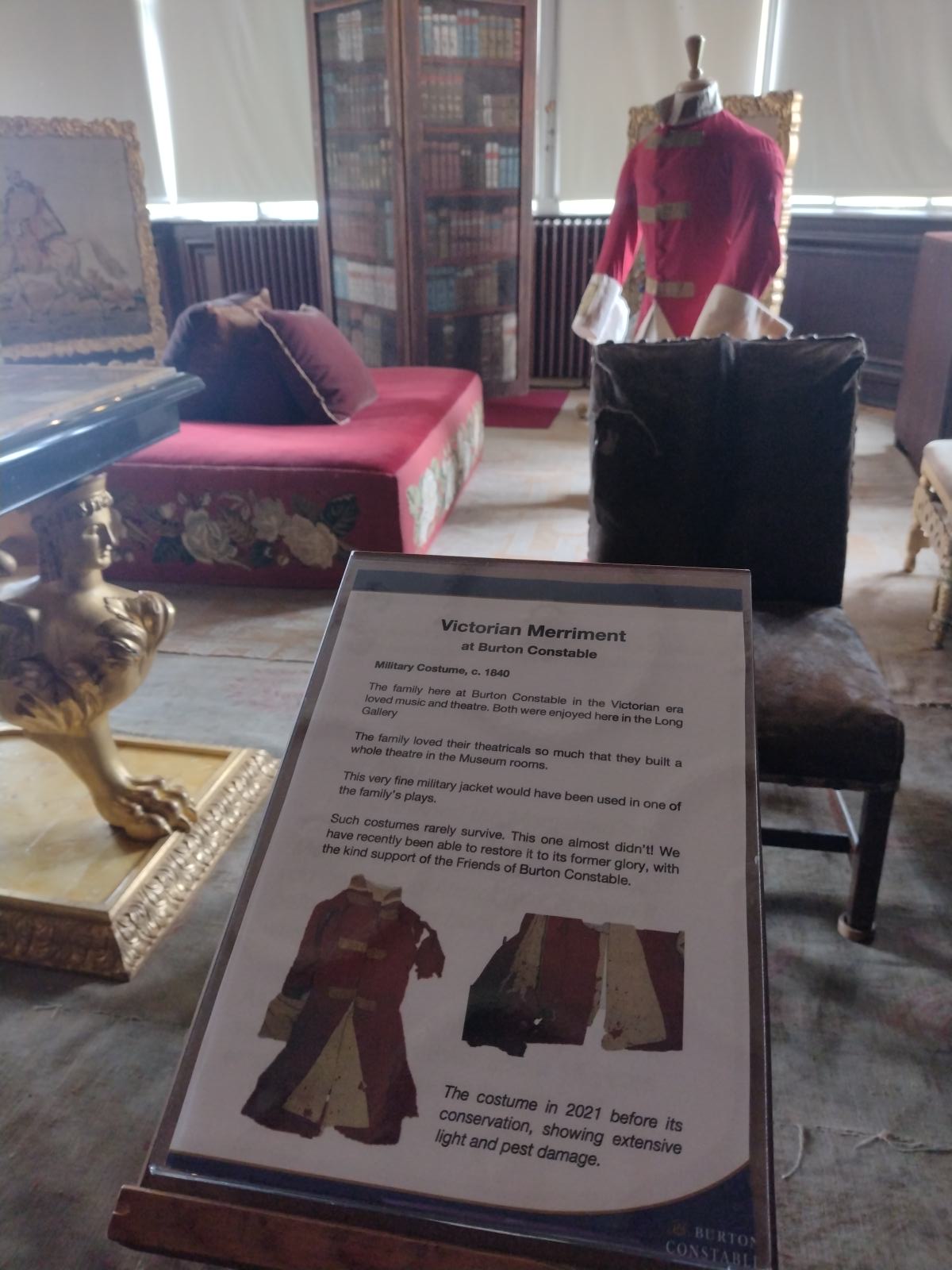

In addition, the collection actually does include unique items, which further ensures this isn’t just another historic house experience. Examples include the French orange tree automaton from 1815, which makes it look as if its birds sing to the music playing; the fantastic carved dragons in the Chinese room, and the Victorian circular occasional wardrobe.

My visit to Burton Constable Hall highlighted again that these places have value precisely for this aesthetic enjoyment, and the associated wellbeing benefits they offer [4]. So, to segment into talking about interpretation, while it is very valid to research and make visible the less than savoury stories behind the wealth that made them possible, I think other places are better suited to sharing that information. Current research suggests that people are there to enjoy the beauty, not to grapple with what might be deeply hurtful personal heritages.

The interpretation

And so I was immensely pleased first of all that the interpretation mentions the family who owned the estate but doesn’t put them centre-stage. They become a generalised vehicle to illustrate and make personal the age in which the house and grounds developed and how this relates to the desires and wishes of the people who lived there at the time. There are photographs from when the family hosted, for example, a ball just before you enter the ballroom, but there is no list of names, no awed ‘here is XY, the original owner of the Hall’. It’s a very light touch that aids your imagination, rather than subtly putting you back on the other side of the social dividing line. In this way, Burton Constable Hall truly becomes a special place for all of us to enjoy.

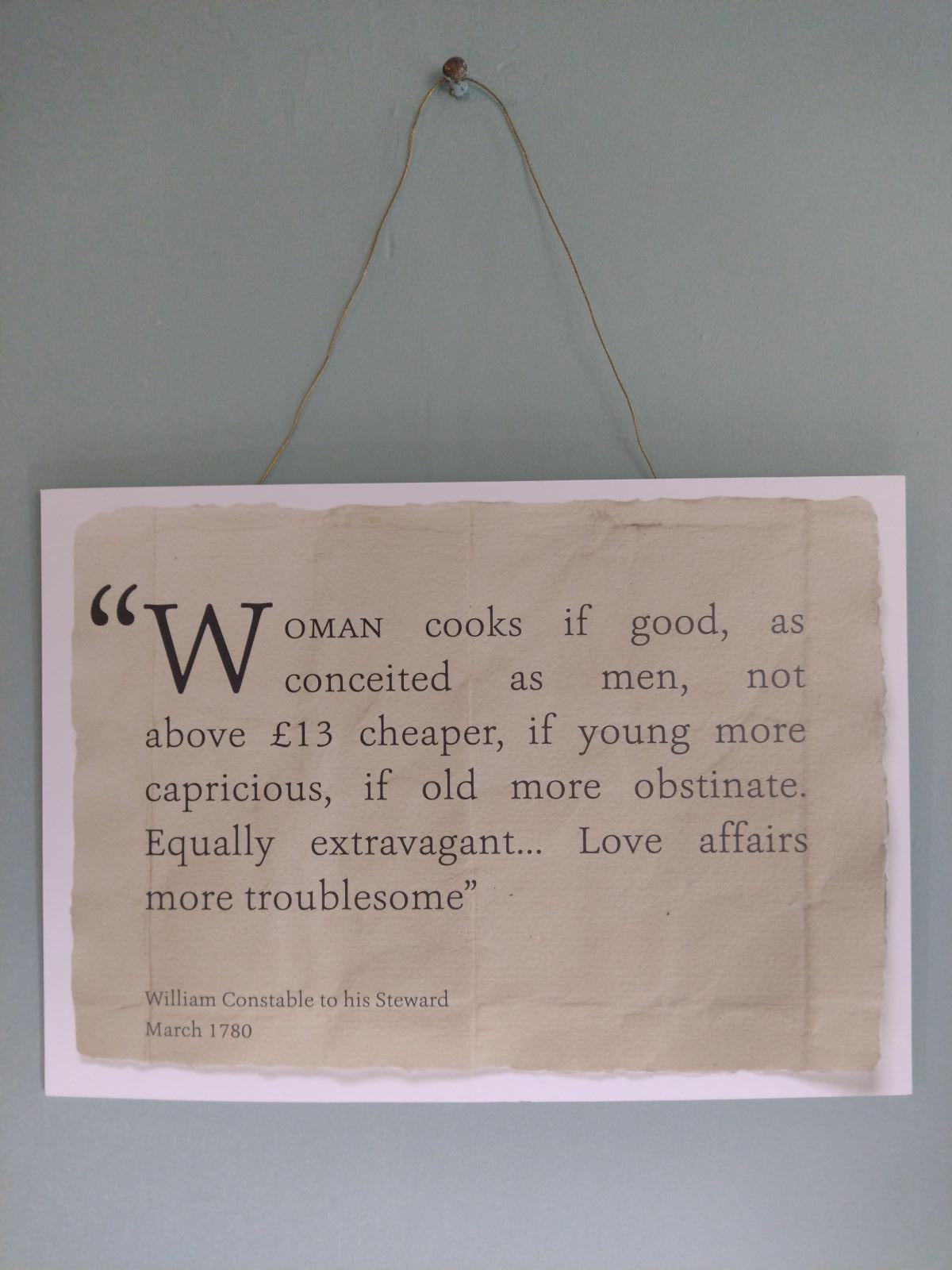

There is a slight emphasis on the by now standard ‘upstairs/downstairs’ narrative, which starts with the first panel one sees just outside the café and continues in the first room one encounters inside the hall itself. However, this manages to highlight personal biographies, of which being in service is just one element in a wider personal context. They also cleverly use quotes from letters, which directs a sharp light onto the sometimes frictional relationship between servants and masters but without being heavy-handed. Those who want to dig deeper into the story of power imbalances will find the information there to do so; those who just want to imagine this building inhabited by people have what they need also.

Throughout the Hall the interpretive panels (which, alongside the room guides, provide the bulk of the interpretation) are written in an easy to understand and slightly humorous tone that never fails to reference the modern perspectives visitors may bring. For example, the panel in the State Bedroom points out that a modern bathroom would have been ‘a luxury even King Henri [who had slept here once] could not have imagined!’

The panels are all orientated toward that which they interpret and include original photographs of the rooms when the house was inhabited. Fairly basic stuff, I hear you say, but seeing how often these days I find myself searching desperately for what panels talk about, this has become a point worth mentioning.

Most panels also suggest an activity for children, or ‘Little Explorers’ as they are called. I didn’t visit with children, but these seemed perfectly suited to keep children engaged and encourage them to think about what they see.

Room Guides

I am not generally a fan of using room guides to provide interpretation, for the simple reason that more often than not they force their own interests on the unsuspecting visitor and disrupt, rather than enhance a visit.

At Burton Constable Hall, however, guides must have been well briefed. They welcomed you with a friendly hello and stepped in when they overheard a question in a conversation between visitors – and of course you could ask them directly about anything that interested you. There was not a whiff of security guard around them, and I perceived them as a very positive presence there to help. I spoke to several of them, and again they made the site feel pleasantly local.

All in all, Burton Constable Hall was an example of how a site should be managed to be welcoming and well-interpreted. What a joy to visit.

Notes

[1] One gripe: descendants of the Chichester-Constable family who sold the house and parkland to the National Heritage Memorial Fund still live in one wing of the house. This continues the story of privilege and exploitation/exclusion/discrimination from which these places originated. While some historic houses have gone down the road to make at least some of these stories visible, I’m not actually interested in that aspect of their history when I go there. I go for the aesthetic value, and being reminded of the origins of this beauty just hacks away at my enjoyment of it. There are other, and better places to talk about it. Or banish it into a stables room if you have to.

[2] The experience at those sites, however, can sometimes begin to feel a bit generic. There is a certain look and feel to them, so much so that I actually refer to the activity of visiting historic homes (in the UK) as ‘National Trusting’.

[3] I may one day dedicate a whole blog post to rules at heritage sites and museums that are either symptoms of the ‘It’s always been like this’ – way of thinking or they are meant to exclude people. Because let’s face it, not allowing dogs in cafés (when others have shown it’s perfectly feasible to welcome them in) excludes their owners. In my book, one should think very carefully about the reason that justifies such exclusion.

[4] In fact, the British National Trust Acts make reference to aesthetic value, and research conducted in 2019 by the National Trust found that when people visit places that are special to them (such as historic buildings), most of them enjoy the scenery and art (77%; p. 9). 61% (ibid) also feel inspired. Of those whose special place was a historic building or garden, only 39% said they felt like they learnt something new (p. 26). I am not convinced this is just a measure of poor interpretation; the other findings suggest that this is about what they seek and gain from their visit.